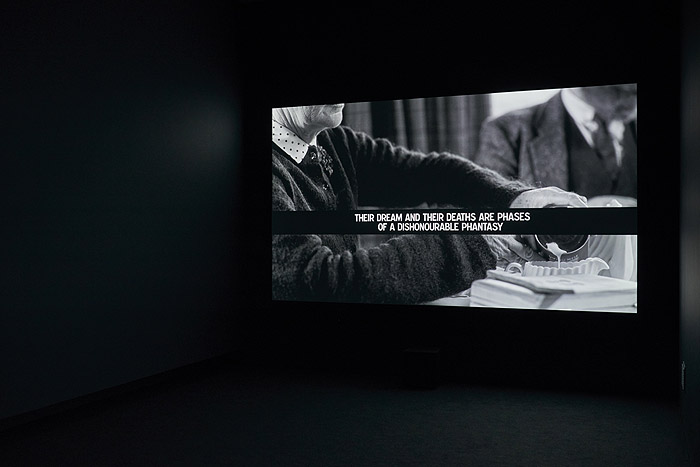

Our Kind, 2016

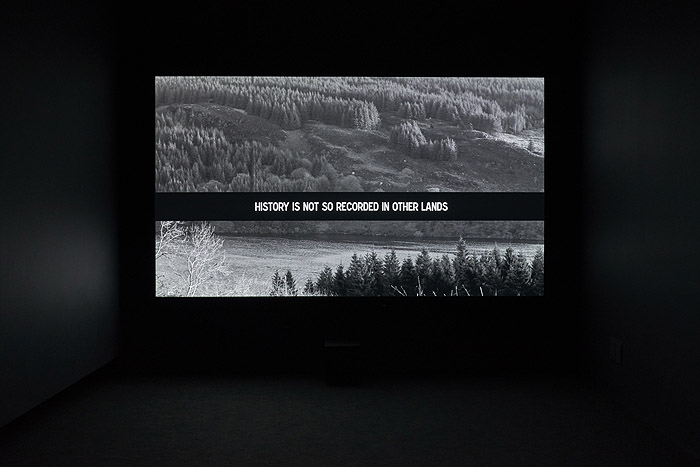

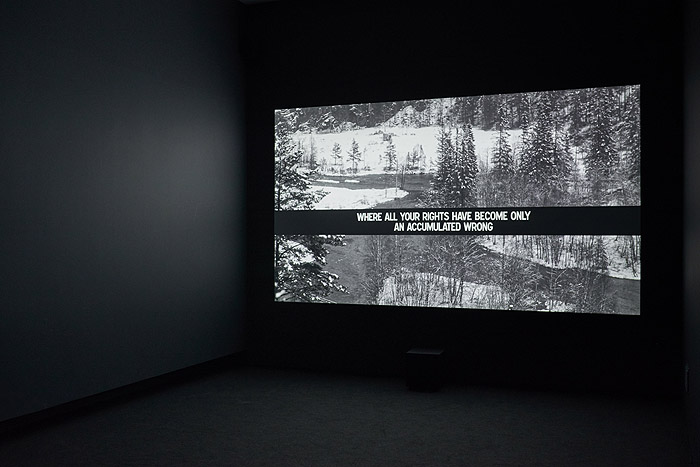

Our Kind imagines a future for Roger Casement had he not been executed in 1916. This film is set twenty-five years later in 1941, where Casement is in exile in Norway with his former manservant and now partner Adler Christensen. They are visited by Alice Stopford Green, a close friend and supporter of Casement. The story unfolds as Adler and Alice both betray their relationships with him, paralleling Casement’s isolation from his homeland, beliefs and the ideals of the Rising.

The film is counterfactual – it is based on real people and facts but presented in a different scenario. This in itself reflects the subjectivity common in the genre of historical drama for film or indeed any historical interpretation. Much of the scholarship surrounding Casement is similarly muddled with subjective romanticism, political prejudices and, even still, an inverted homophobia that cannot come to terms with Casement’s personal and public lives. Several of these angles are woven into the story albeit mis-represented, unexplained and ambiguous.

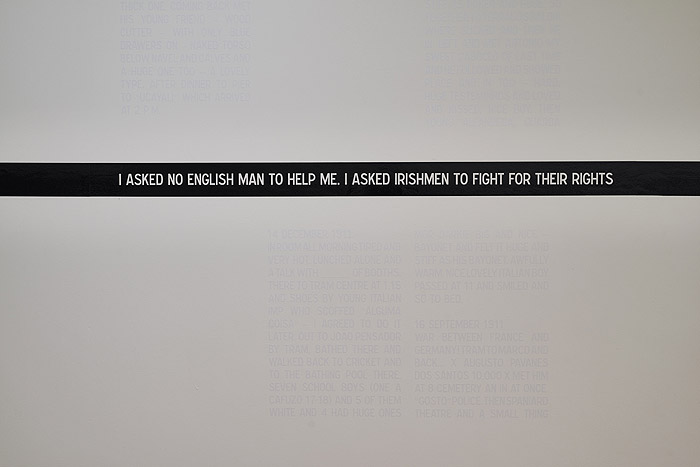

Our Kind gets its title from the iconic speech Casement made on his conviction, and extracts of this speech are used in the film, giving the words new meaning. Similarly, the dialogue re-narrativises subtitles from another film, which like other recent work by Phelan is not openly credited here. Instead the re-staging of the text and dialogue drawn from these sources creates a whole new story. Through apparatus of cinema, the film embraces a complex history and presents a story that needs to be read between the lines. This reflects an outcome of the Rising rather than re-creating or re-enacting an idea of what that history possibly was.

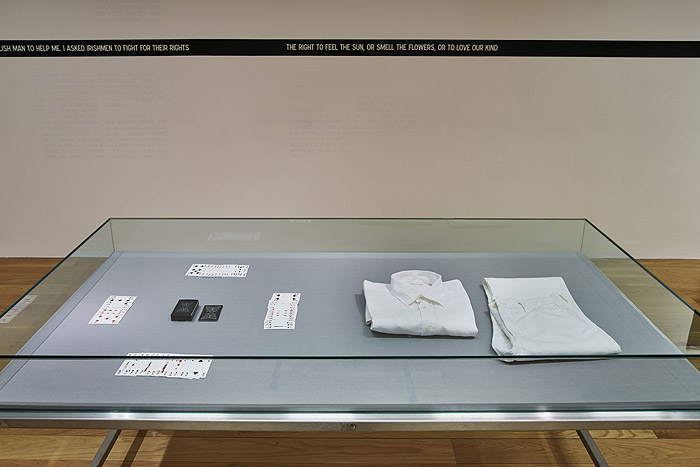

The other works in Gallery 10 attest to the real Casement but again are highly subjective. Extracts from his private, so called, Black Diaries, are presented as white on white wall text. This simple act reveals yet conceals, using full unedited daily entries from published sources. Some of the extracts used here were circulated by the British government during the Appeal and resulted in the loss of public support for Casement. The work in the vitrine touches on the humanitarian yet colonial and imperialist aspects of Casement’s career. The piece is a portrait of the two native Indians from Putamayo who were brought briefly to Britain by Casement in 1910 are represented here by the items for which they were exchanged or purchased for, rather than the actual photographs or painting made of them.

Alan Phelan

February 2016