Ralph Eamon Odo Barbara, 2007

mother’s tankstation, Dublin

19 Sept – 27 Oct 2007

“Everything around me moves. Nothing is ever what it seems to be, everything is subject to constant metamorphosis, it all changes unexpectedly, and with lightening swiftness…” Guillaume Apollinaire

It is if Apollinaire has found himself, unexpectedly, in the recreational quarters of Odo the shape-shifter from a particularly tangential TV episode of Deep Space Nine. Unlikely, yes, but no more so than the formal, spatial and temporal shifts of meaning that occur in Alan Phelan’s installation Ralph, Eamon, Odo, Barbara, at mother’s tankstation. Wherein Phelan synthesises Aristotolean acceptance of the ‘given’ with a Platonic readiness to hypothesize a different reality, a different realm. In simpler terms, Phelan simultaneously employs and subverts the ‘it does what it says on the tin’ approach to the world. Whilst Phelan’s individual sculptures accord to expected taxonomic systems of naming (i.e. Barbara refers to Barabra Hepworth, Eamon stands for Eamon DeValera, Odo is the above mentioned slippery customer, ‘Odo’ – who only ever really manages approximate copies of things, and Ralph equals Ralph Gifford – who? – we will come back to him) and apply appropriate expected meaning, they also employ radical shifts of lateral logic.

This logic-shifting allows Phelan to perform acrobatic connective associations with any sort of idea or meaning he so desires. Crucially, Phelan locks his distortions into patterns of actual and historical events, ideas, things and places. One leads us to another, and all we have to do to follow Phelan’s train of thought is to perform similar acts of mental shape-shifting, based upon a series of keys and clues scattered around the installation, much like the assisting props in Odo’s private chamber.

This is where Ralph (Gifford) comes into the equation. Phelan is perhaps best known for working within self-imposed models of particularised research, where ideas need to move coherently from A-Z, commonly beginning his projects based upon specific research. In this instance Phelan commences with a number of little-known documentary photographs of American soldiers stationed on Whiddy Island naval base during WW1, but ends up with an irreverent parody of situationalism, revelling in tenuous things that deliciously, hardly make sense.

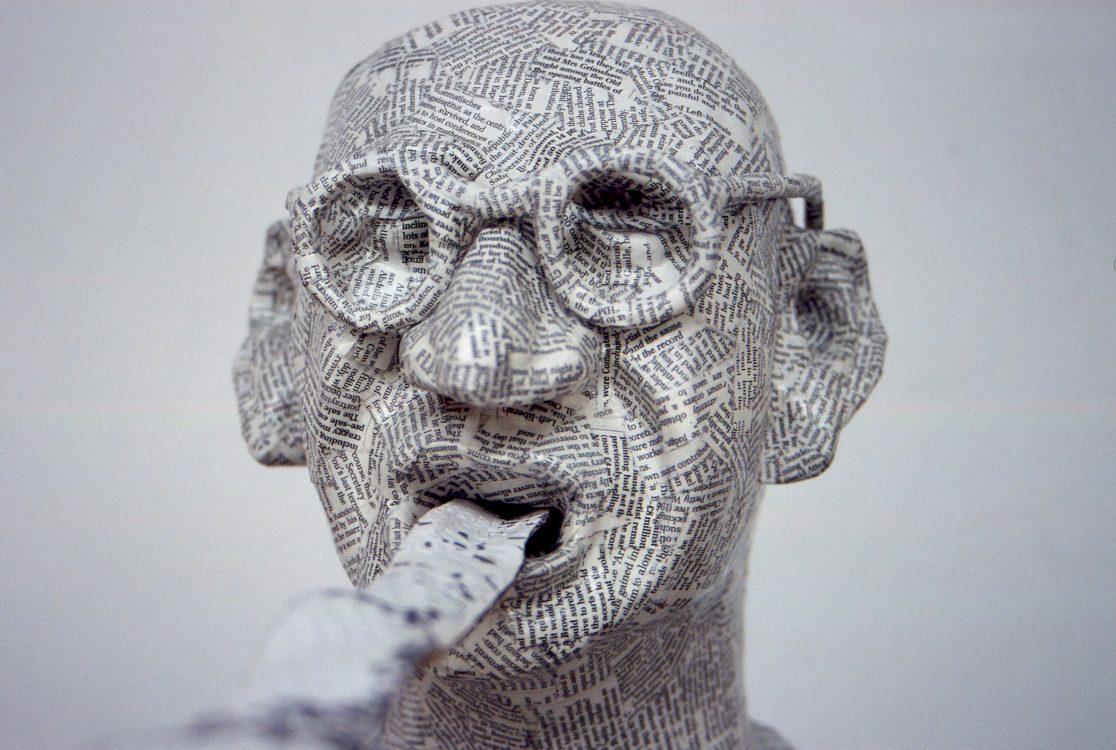

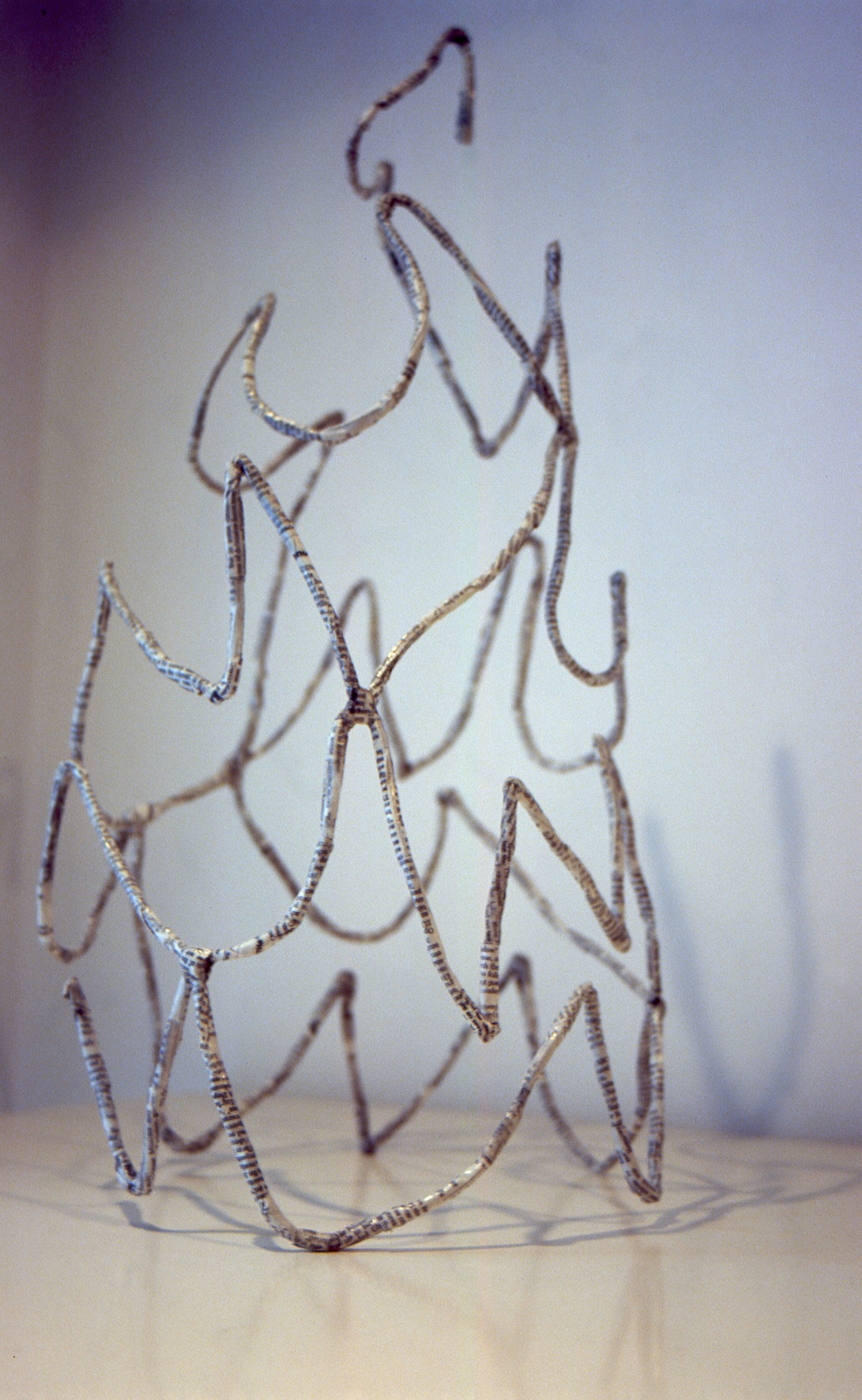

Phelan, in turn emulates Odo’s unwillingness to enter into specifics, which leaves us, the viewer, with simplified forms, rounded, modernist, Hepworthian approximations of known structures. From here on in Phelan’s visual language erupts into playfulness (puns, paraody, satire) and takes its greatest delight in unmasking the deceptions of appearances. A blow-up hen-party doll becomes an approximate Hepworth ‘Mother and Child’ morphing off its own plinth. A papier-mâché bust of DeValera visually speaks in tongues, a similar poe-faced portrait of Arthur Griffith has partially mutated into a troublesome mosquito. While all Phelan’s works are made motivated by historical or personal narratives, this no longer matters, the unexpected metamorphosis has already begun, like Apollinaire, we must go with it or be left behind. Phelan is on a role, his past is our present and our Buckminster Fuller future beckons, illuminated by a glowing Death Star. Odo has already left the building, leaving only a copy of his ear.