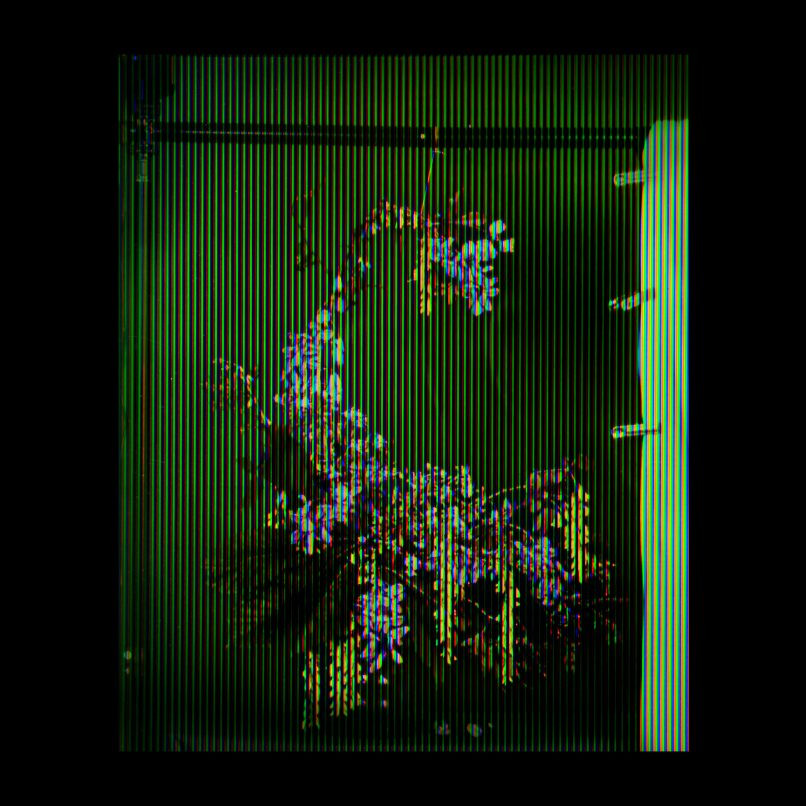

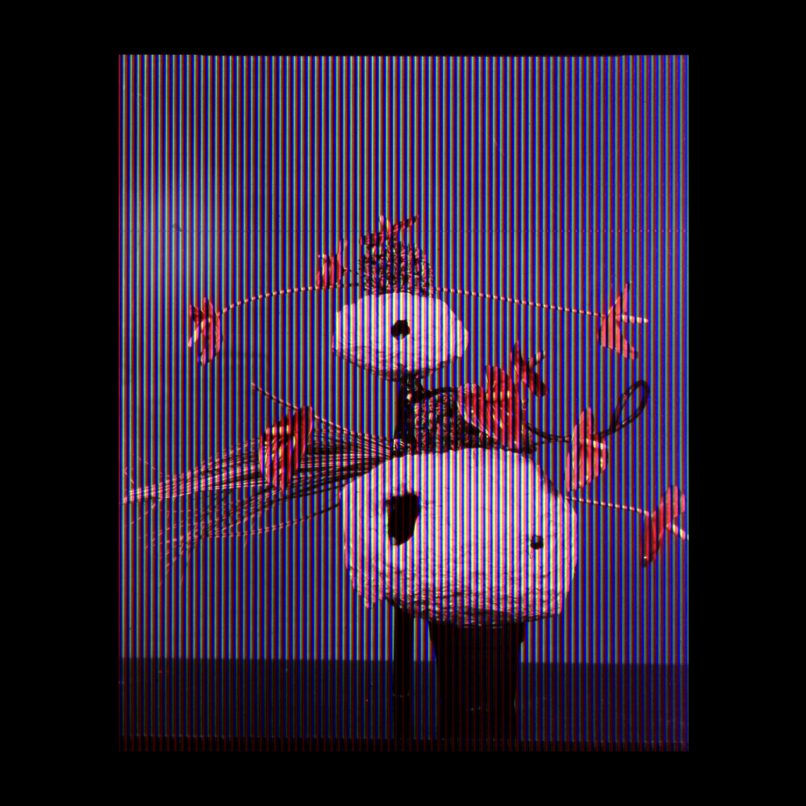

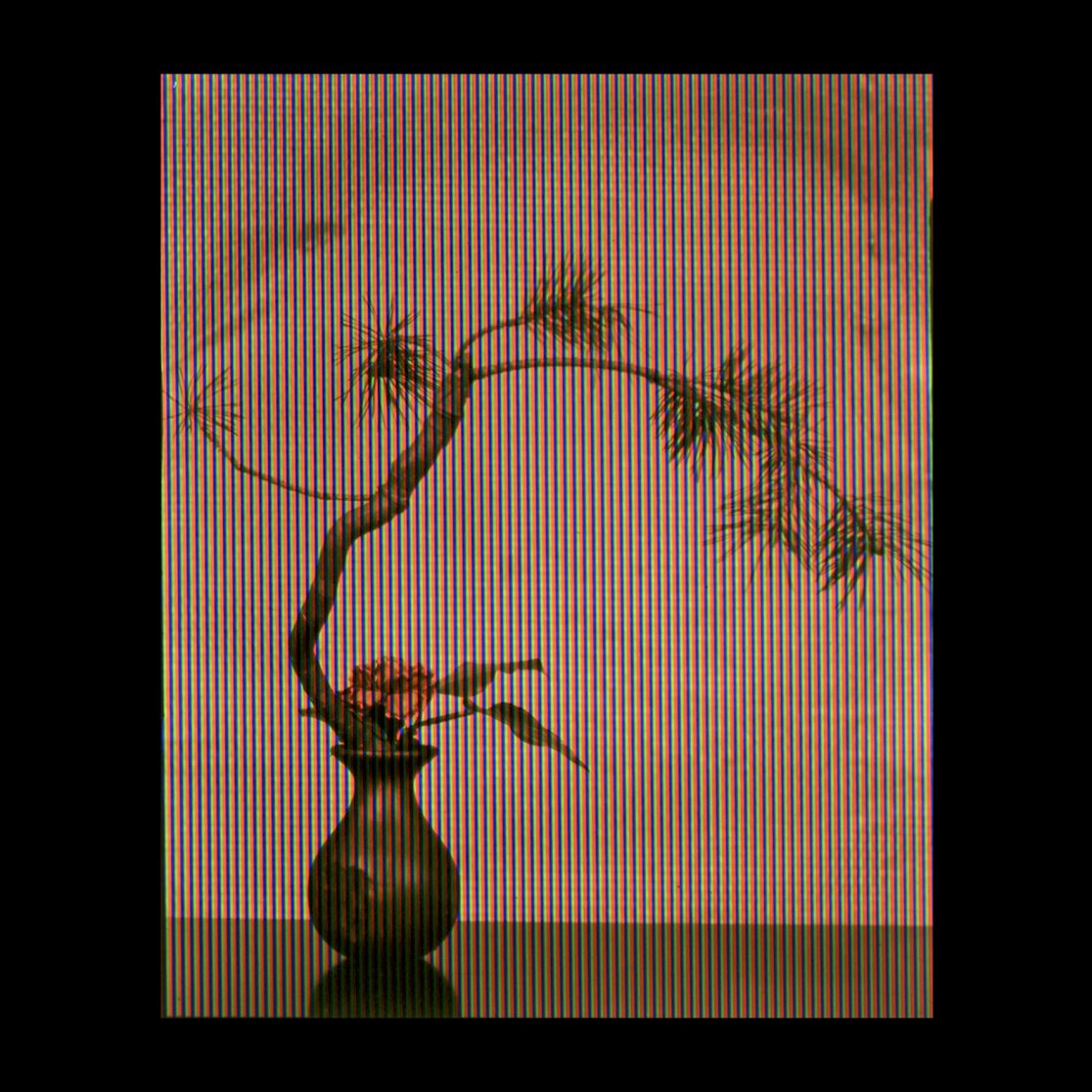

Fleurs Tarabiscoté, 2021

Molesworth Gallery, Dublin

8-31 July 2021

The title of the show translates as fussy, complex, over-ornate, or simply florid flowers – pointing to these photographs being more than just about blooms. The exhibition presents fifteen unique, non-editioned, Joly screen photographs of flower arrangements using the nineteenth century colour process invented in Dublin and revived by Phelan, as seen in exhibitions over the past two years at the RHA, Dublin; CCI, Paris; Void, Derry and The Dock, Carrick-on-Shannon.

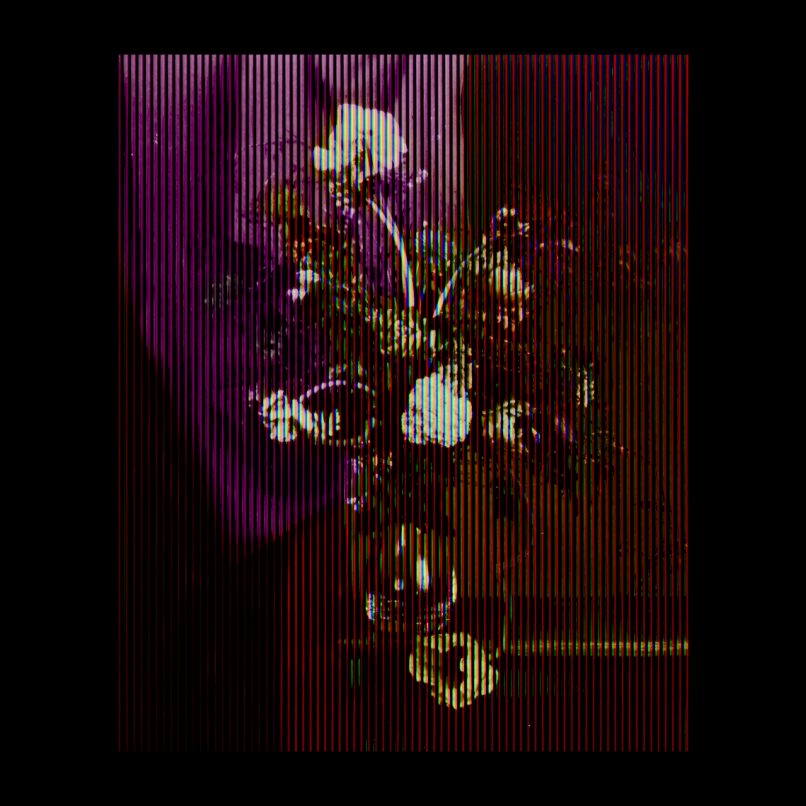

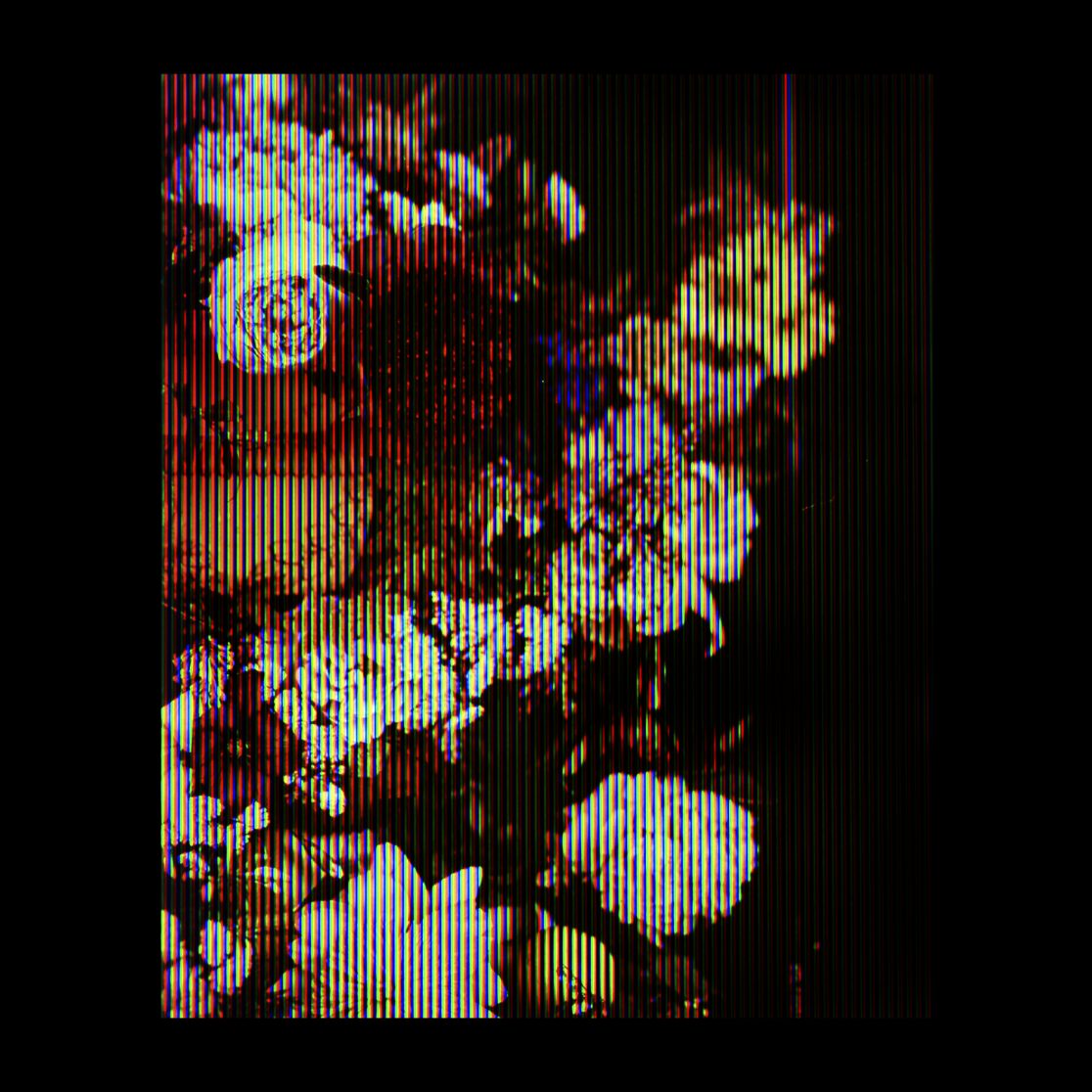

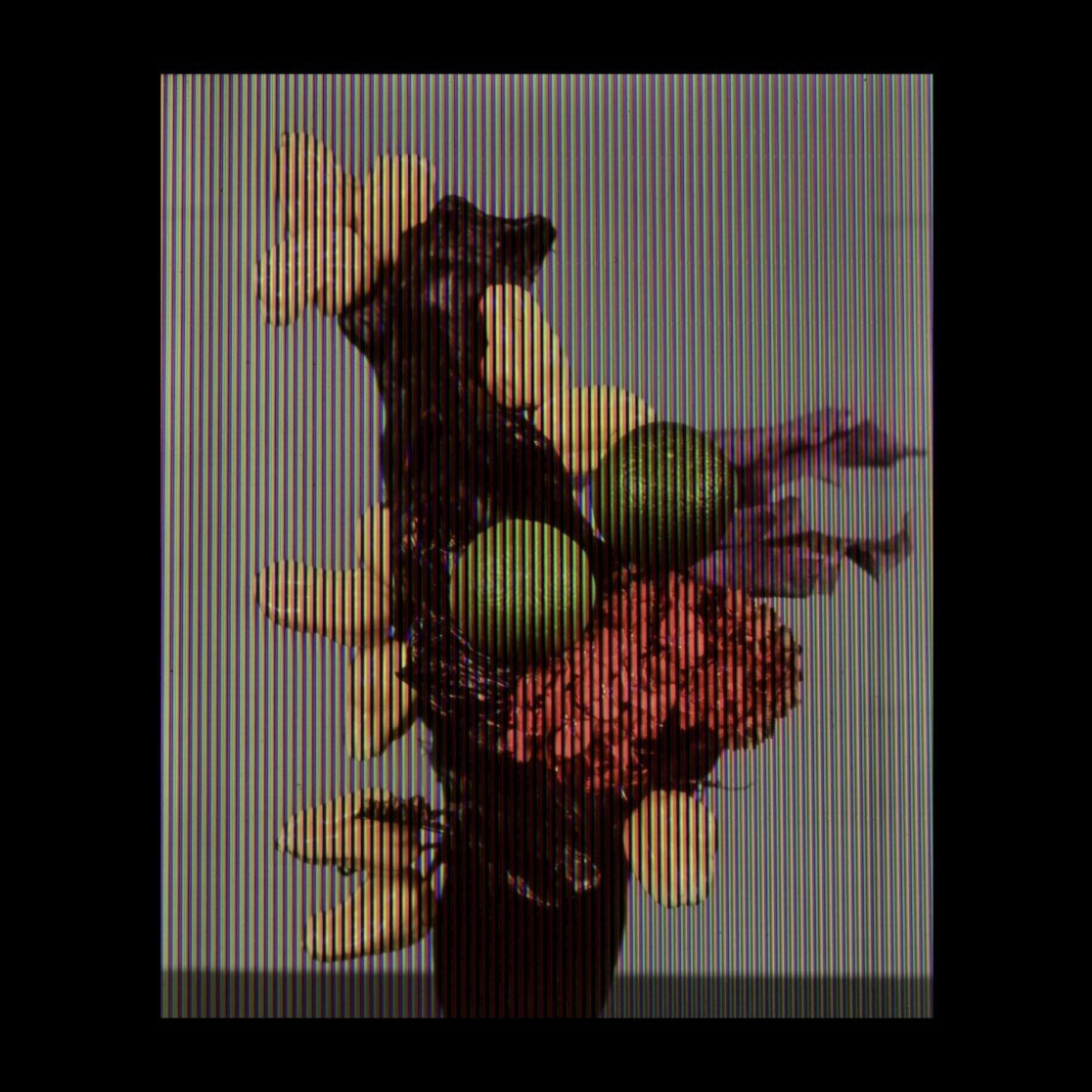

The photographs are small 4×5 sheet film sized images as they comprise of the sheet film from a large format camera and a digitally printed colour screen the same size. The Joly screen process is not a chemical process but instead filters light on exposure and display to create colour. The screen is made up of red, green and blue stripes giving the photographs a very distinctive appearance. Invented by TCD physics professor John Joly in the 1890s, the two-layer photograph also creates a colour shift upon viewing, similar to lenticular prints. These small photographs have the intensity of painted miniatures, illuminated by LED panels, demanding a slowing down in viewing, with a rich array of visual and historical reference points.

The images have nostalgic feel given muted colours and the content which are based on historic flower paintings. These works were made in collaboration with Dunboyne Flower and Garden Club. For Phelan this was also an opportunity to expand his interest in participatory practices – art making that involves working with others to expand the notion of authorship into a shared activity. Exotic flowers were made-up from domestic Irish gardens and German supermarkets, assembled to resemble abundant Baroque designs and exotic Spring bulbs. Seasonal blooms were also maximised over the 9 months that these images were made during.

With this body of work Phelan imagines a visual history the Joly screen never had, as the process was abandoned from use in the early twentieth century. To do this, he uses art and historical references spanning over 500 years. The work presents a “counterfactual temporality”, a longer potential history for photography that contextualises it prior to its technical beginnings.

Work titles name the source artist, year of their activity and a related historical event. The works do not seek to perfectly re-create or re-appropriate but construct a flawed approximate, out-of-sync and yet connected to a related flow of events. For example, it should be impossible to look at the Dutch Golden Age flower paintings without acknowledging the Tulip Mania that swept the financial markets, laying the foundations for the boom/bust economic cycle. Indeed the cultivation of flowers mirror the rise of the bourgeoisie in early Western imperial and colonial travels and land grabs, charting not so innocent trades routes, that are now the subject of much discussion and revision in decolonising Western art traditions.

The references are subtle but the direction of interpretation moves away from mere aesthetics. The photorealism of much flower painting belies the mixed-seasons of specimens on show and oddly negates the creativity required by the artists in assembling these painted arrangements. Similarly the history of floral art is often dismissed as craft. The thematic categories in contemporary flower arranging competitions however, require imaginative and conceptual leaps that are not dissimilar from art yet function and operate in parallel worlds.

The inherent ambiguity of the images ghosts a history the process never had a chance to image or imagine. Convoluted titles attempt to navigate possible interpretative paths but they only leave echoes of a past that never happened and a present that has still more to achieve or reveal.